Summary of Findings

Younger Americans—those ages 16-29—exhibit a fascinating mix of habits and preferences when it comes to reading, libraries, and technology. Almost all Americans under age 30 are online, and they are more likely than older patrons to use libraries’ computer and internet connections; however, they are also still closely bound to print, as three-quarters (75%) of younger Americans say they have read at least one book in print in the past year, compared with 64% of adults ages 30 and older.

Similarly, younger Americans’ library usage reflect a blend of traditional and technological services. Americans under age 30 are just as likely as older adults to visit the library, and once there they borrow print books and browse the shelves at similar rates. Large majorities of those under age 30 say it is “very important” for libraries to have librarians as well as books for borrowing, and relatively few think that libraries should automate most library services, move most services online, or move print books out of public areas.

At the same time, younger library visitors are more likely than older patrons to access the library’s internet or computers or use the library’s research resources, such as databases. And younger patrons are also significantly more likely than those ages 30 and older to use the library as a study or “hang out” space: 60% of younger patrons say they go to the library to study, sit and read, or watch or listen to media, significantly more than the 45% of older patrons who do this. And a majority of Americans of all age groups say libraries should have more comfortable spaces for reading, working, and relaxing.

Younger Americans’ use of technology

Compared with older adults, Americans under age 30 are just as likely to have visited a library in the past year (67% of those ages 16-29 say this, compared with 62% of adults ages 30 and older), but they are significantly more likely to have either used technology at libraries or accessed library websites and services remotely:

- Some 38% of Americans ages 16-29 have used computers and the internet at libraries in the past year, compared with 22% of those ages 30 and older. Among those who use computers and internet at libraries, young patrons are more likely than older users to use the library’s computers or internet to do research for school or work, visit social networking sites, or download or watch online video.

- Almost half (48%) of Americans ages 16-29 have ever visited a library website, compared with 36% of those ages 30 and older (who are significantly less likely to have done so).1

- Almost one in five (18%) Americans ages 16-29 have used a mobile device to visit a public library’s website or access library resources in the past 12 months, compared with 12% of those ages 30 and older.

The higher rates of technology use at libraries by those under age 30 is likely related to their heavier adoption of technology elsewhere in their lives. In the late-2012 survey analyzed in this report, over nine in ten younger Americans owned a cell phone, with the majority owning a smartphone; some 16% owned an e-reader, and 25% owned a tablet computer.

The high figures for technology adoption by young adults is also striking in more recent surveys by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (surveys that covered those 18 and older, cited here for reference):

- 98% of young adults ages 18-29 use the internet and 80% have broadband at home2

- 97% of young adults ages 18-29 own a cell phone and 65% own a smartphone3

- 34% of young adults ages 18-29 have a tablet computer4

- 28% of young adults ages 18-29 own an e-reader5

Focusing back on younger Americans ages 16-29 from our November 2012 survey, we find that their interest in technology is reflected in their views about library services: 97% of Americans under age 30 say it is important for libraries to provide free computer and internet access to the community, including 75% who say it is “very important.”

E-book reading habits over time

As with other age groups, younger Americans were significantly more likely to have read an e-book during 2012 than a year earlier. Among all those ages 16-29, 19% read an e-book during 2011, while 25% did so in 2012. At the same time, however, print reading among younger Americans has remained steady: When asked if they had read at least one print book in the past year, the same proportion (75%) of Americans under age 30 said they had both in 2011 and in 2012.

In fact, younger Americans under age 30 are now significantly more likely than older adults to have read a book in print in the past year (75% of all Americans ages 16-29 say this, compared with 64% of those ages 30 and older). And more than eight in ten (85%) older teens ages 16-17 read a print book in the past year, making them significantly more likely to have done so than any other age group.

Library habits and priorities for libraries

The under-30 age group remains anchored in the digital age, but retains a strong relationship with print media and an affinity for libraries. Moreover, younger Americans have a broad understanding of what a library is and can be—a place for accessing printed books as well as digital resources, that remains at its core a physical space.

Overall, most Americans under age 30 say it is “very important” for libraries to have librarians and books for borrowing; they are more ambivalent as to whether libraries should automate most library services or move most services online. Younger Americans under age 30 are just as likely as older adults to visit the library, and younger patrons borrow print books, browse the shelves, or use research databases at similar rates to older patrons; finally, younger library visitors are more likely to use the computer or internet at a library, and more likely to see assistance from librarians while doing so.

Additionally, younger patrons are significantly more likely than older library visitors to use the library as a space to sit and ready, study, or consume media—some 60% of younger library patrons have done that in the past 12 months, compared with 45% of those ages 30 and older. And most younger Americans say that libraries should have completely separate locations or spaces for different services, such as children’s services, computer labs, reading spaces, and meeting rooms: 57% agree that libraries should “definitely” do this.

Along those lines, patrons and librarians in our focus groups often identified teen hangout spaces as especially important to keep separate from the main reading or lounge areas, not only to reduce noise and interruptions for other patrons, but also to give younger patrons a sense of independence and ownership. A library staff member in our online panel wrote:

“Having a separate children’s area or young adults area will cater solely to those groups and make them feel that the library is theirs. They do not have to deal with adults watching them or monitoring what book they pick or what they choose to do—it’s all about them and what they want with no judgment. Children and teens love having their own space so why not give them that at the library?”

Younger Americans’ priorities for libraries reflect this mix of habits, including various types of brick-and-mortar services as well as digital technologies. Asked about what it is “very important” libraries should offer, for instance, librarians were at the top of the list:

- 80% of Americans under age 30 say it is ��very important” for libraries to have librarians to help people find information they need

- 76% say it is “very important” for libraries to offer research resources such as free databases

- 75% say free access to computers and the internet is “very important” for libraries to have

- 75% say it is “very important” for libraries to offer books for people to borrow

- 72% say quiet study spaces are “very important”

- 72% say programs and classes for children and teens are “very important” for libraries to have

- 71% say it is “very important” for libraries to offer job or career resources

However, even as young patrons are enthusiastic users of libraries, they are not as likely to see it as a valuable asset in their lives. Even though 16-17 year-olds rival 30-49 year-olds as the age groups most likely to have used a library in the past year, those in this youngest age group are less likely to say that libraries are important to them and their families. Parents and adults in their thirties and forties, on the other hand, are more likely to say they value libraries, and are more likely than other Americans to use many library services.

Attitudes toward current and future library services

When it comes to questions about the kinds of services libraries should offer, the top priorities of younger adults are that libraries should coordinate more with schools and offer free literacy programs, the same as older adults.

Younger Americans’ priorities for libraries also mirror those of older adults in other measures. For instance, 80% of Americans under age 30 say that librarians are a “very important” resource for libraries to have (along with 81% of adults ages 30 and older). Other resources ranked “very important” by Americans under age 30 include:

- Research resources such as free databases (76%)

- Free access to computers and the internet (75%)

- Books for borrowing (75%)

- Quiet study spaces (72%)

- Programs and classes for children and teens (72%)

- Job or career resources (71%)

Finally, when given a series of questions about possible new services at libraries, Americans ages 16-29 expressed the strongest interest in apps that would let them locate library materials within the library or access library services on their phone, as well as library kiosks that would make library materials available throughout the community. In addition, younger respondents were somewhat more likely than older adults to say they would be likely to use personalized online accounts, digital media labs, and pre-loaded e-readers.

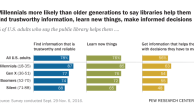

The following chart shows the differences between age groups that emerged when respondents were asked about the future of libraries.

A snapshot of younger Americans’ reading and library habits

Reading habits

Some 82% of Americans ages 16-29 read at least one book in any format in the previous 12 months. Over the past year, these younger readers consumed a mean (average) of 13 books—a median (midpoint) of 6 books.

- 75% of Americans ages 16-29 read at least one book in print in the past year

- 25% read at least one e-book

- 14% listened to at least one audiobook

Library use

As of November 2012:

- 65% of Americans ages 16-29 have a library card.

- 86% of those under age 30 have visited a library or bookmobile in person; over half (58%) have done so in the past year.

- 48% of those under age 30 have visited a library website; 28% have done so in the past year.

- 18% of those under age 30 have visited library websites or otherwise accessed library services by mobile device in the past 12 months.

Among recent library users under age thirty (that is, Americans ages 16-29 who have visited a library, library website, or library’s mobile services in the past year), 22% say their overall library use has increased over the past five years. Another 47% said it had stayed about the same, and 30% said it had decreased over that time period.

About this research

This report explores the changing world of library services by exploring the activities at libraries that are already in transition and the kinds of services citizens would like to see if they could redesign libraries themselves. It is part of a larger research effort by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project that is exploring the role libraries play in people’s lives and in their communities. The research is underwritten by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

This report contains findings from a survey of 2,252 Americans ages 16 and above between October 15 and November 10, 2012. The surveys were administered half on landline phones and half on cell phones and were conducted in English and Spanish. The margin of error for the full survey is plus or minus 2.3 percentage points. More information about the survey is available in the Methods section at the end of this report.

There were several long lists of activities and services in the phone survey. In many cases, we asked half the respondents about one set of activities and the other half of the respondents were asked about a different set of activities. These findings are representative of the population ages 16 and above, but it is important to note that the margin of error rises when only a portion of respondents is asked a question. The number of respondents in each group or subgroup is noted in the charts throughout the report.

In addition, we quote librarians and library patrons who participated in focus groups in person and online that were devoted to discussions about library services and the future of libraries. Our in-person focus groups were conducted in Chicago, Illinois; Denver, Colorado; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Baltimore, Maryland in late 2012 and early 2013.

Other quotes in this report come from an online panel canvassing of librarians who have volunteered to participate in Pew Internet research. Over 2,000 library staff members participated in the online canvassing that took place in late 2012. No statistical results from that canvassing are reported here because it was an opt-in opportunity meant to draw out comments from patrons and librarians, and the findings are not part of a representative, probability sample. Instead, we highlight librarians’ written answers to open-ended questions that illustrate how they are thinking about and implementing new library services.

Age group definitions

For the purposes of this report, we define younger Americans as those ages 16-29, although we will use several different frameworks for this analysis. At times we will compare all those ages 16-29 to all older adults (ages 30 and older). When more fine-grained analysis reveals important differences, we will divide younger readers into three distinct groups: high-schoolers (ages 16 and 17); college-aged adults (ages 18-24) who are starting their post-secondary life; and adults in their later twenties (ages 25-29) who are entering jobs and careers.6 For more information about these older age groups, please see our earlier report, Library Services in the Digital Age.

Acknowledgements

About the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project is an initiative of the Pew Research Center, a nonprofit “fact tank” that provides information on the issues, attitudes, and trends shaping America and the world. The Pew Internet Project explores the impact of the internet on children, families, communities, the work place, schools, health care and civic/political life. The Project is nonpartisan and takes no position on policy issues. Support for the Project is provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts. More information is available at pewresearch.org/pewresearch-org/internet.

Advisors for this research

A number of experts have helped Pew Internet in this research effort:

Daphna Blatt, Office of Strategic Planning, The New York Public Library

Richard Chabran, Adjunct Professor, University of Arizona, e-learning consultant

Larra Clark, American Library Association, Office for Information Technology Policy

Mike Crandall, Professor, Information School, University of Washington

Catherine De Rosa, Vice President, OCLC

LaToya Devezin, American Library Association Spectrum Scholar and librarian, Louisiana

Amy Eshelman, Program Leader for Education, Urban Libraries Council

Sarah Houghton, Director, San Rafael Public Library, California

Mimi Ito, Research Director of Digital Media and Learning Hub, University of California Humanities Research Institute

Michael Kelley, Editor-in-Chief, Library Journal

Patrick Losinski, Chief Executive Officer, Columbus Library, Ohio

Jo McGill, Director, Northern Territory Library, Australia

Dwight McInvaill, Director, Georgetown County Library, South Carolina

Bobbi Newman, Blogger, Librarian By Day

Carlos Manjarrez, Director, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Institute of Museum and Library Services

Johana Orellana-Cabrera, American Library Association Spectrum Scholar and librarian in Texas.

Mayur Patel, Vice President for Strategy and Assessment, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

Global Libraries staff at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Gail Sheldon, Director, Oneonta Public Library (Alabama)

Sharman Smith, Executive Director, Mississippi Library Commission

Disclaimer from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

This report is based on research funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.